EPBD: Time for political courage to protect citizens

As originally published on Euractiv.com

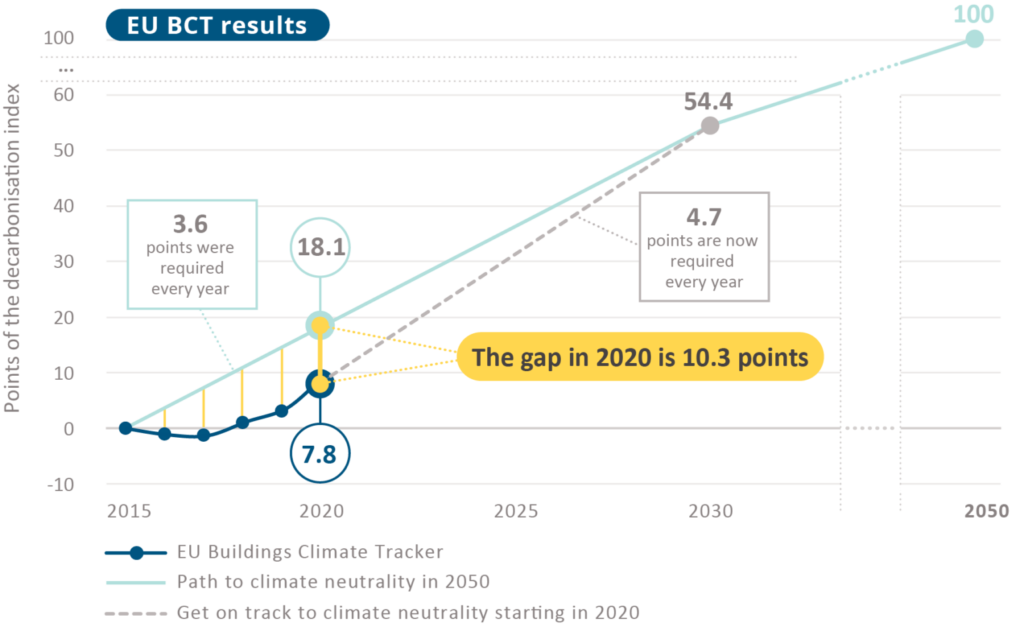

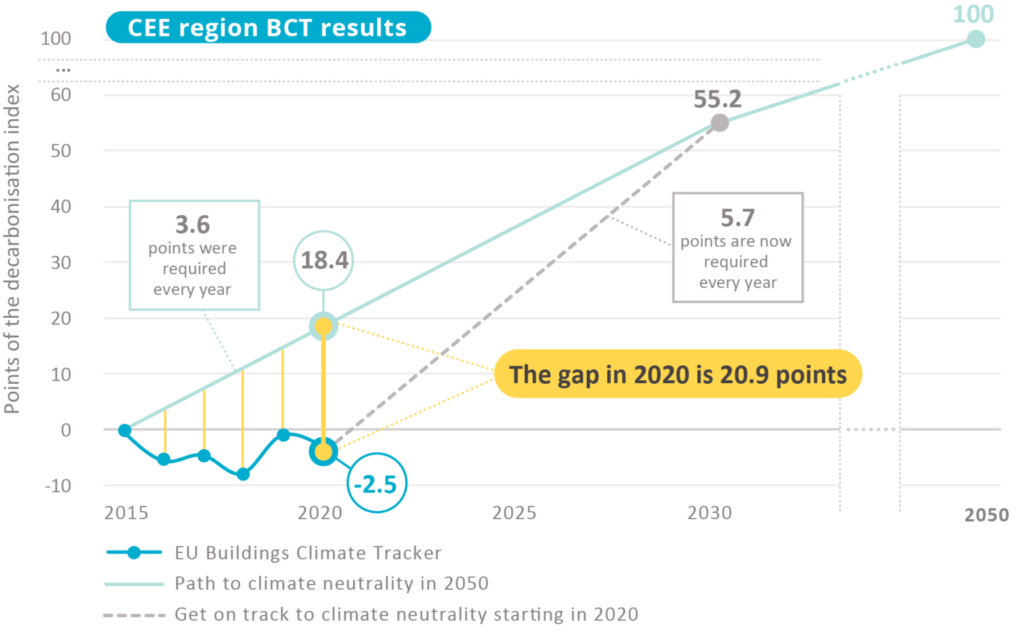

Europe’s cornerstone legislation on buildings, the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD), has entered the last phase of the decision-making process, the negotiations between the EU Commission, Parliament and Council (known in EU speak as ‘trilogues’). This means it’s crunch time for EU buildings legislation.

Europe is facing many complex problems. Climate change, getting off fossil fuels and achieving energy independence, soaring prices for heating, and energy poverty are all issues for which building policies can provide solutions.

However, we are running against the clock. Considering the lengthy legislative process, the trilogues must result in legislation that will deliver big results. We need to decarbonise our buildings, and we must protect the millions of Europe’s citizens living in leaky and wasteful buildings against soaring energy bills.

So where do our institutions stand, and what direction should policymakers take as they grapple over the details? BPIE’s recent analysis suggests that Parliament provides the best approach to meet our decarbonisation targets, and should be considered as the starting point in trilogues.

Standards for new buildings should be clear and effective

According to a forthcoming technical study authored by Ramboll, BPIE and KU Leuven, new constructions are expected to increase the floor area of the EU building stock by 40% by 2050. This is a huge projected growth with big potential consequences if effective strategies aren’t put in place now. This expansion will require heating and cooling of a greater floor area; potential reductions in operational emissions will be partly cancelled out by increased built space.

Europe’s architects, engineers and construction sector therefore need a clear zero emission building (ZEB) standard to align the design and construction of future builds with the goal of climate neutrality.

To ensure high performance, new building standards should include low and well-defined maximum levels for energy demand, and energy should be supplied from 100% renewable sources, with a minimum share of this energy produced onsite or nearby in order to avoid costly investments in an inefficient grid.

Without a strict cap on energy demand, a new building could be easily classified as zero emission as long as it’s plugged into renewables with little to no improvement to operational efficiency and without a local production of renewable energy. As a consequence, occupants would not be likely to benefit from reduced energy bills, and investments in increased energy supply would become unnecessarily high.

Related to this, the Council adds carbon free energy as an eligible energy source. However, carbon free does not mean renewable. This difference in language can lead to important environmental and economic consequences; numerous energy sources fall in this grey area. If this wording passes, Europe will effectively be locking itself into potentially huge investments in energy supply and infrastructure that are misaligned with our environmental priorities. Carbon free should therefore be removed from the text and the zero emission standard should explicitly require that energy supply comes from only renewable sources produced onsite or nearby.

Minimum energy performance standards (MEPS) are a new addition to the EPBD. The instrument means to ensure that the worst-performing buildings are renovated so that occupants can live in healthy homes with affordable energy bills.

Parliament’s MEPS scheme gives a strong boost to renovation and is better for citizens. It includes a higher number of buildings, indicates a clear target to reach for each building, increases energy performance to a higher level, spurs action in the early 2030s, and embeds MEPS obligations into an enabling framework of financial support, advisory services, and social safeguards.

It also lays out a series of potential exemptions, meaning that contrary to popular belief, Member States will not be forced to do the impossible. On the contrary, they will have a lot of freedom to implement the system reflecting national circumstances. This approach should be the baseline in negotiations.

However, minimum standards have become highly politicised, and acceptance varies greatly across countries. Some are effectively waging a populistic war against MEPS.

It is therefore not surprising that Council has significantly watered down the original proposal, reducing the scope and introducing vague language on which residential buildings must be renovated.

In truth, this lukewarm approach will aggravate social cleavages. It would signal to the construction and financial sectors to focus on larger buildings and avoid investing in residential. Indeed, designing MEPS well is a complex exercise, but reducing them down to a set of unclear guidelines will only block renovation from the people who need it most, quite literally leaving them in the cold.

Also worrying, neither Council nor Parliament incentivise renovation to go beyond the bare minimum. We should rather resolve to lift the worst-performing buildings up to the highest-performing classes. The directive must not lock-in the ‘second-worst-performing’ buildings as the desirable renovation result! This point should be treated with priority.

Member states: be bold for your citizens

Our assessment shows that Parliament is coming to the table with the most workable framework to decarbonise the building stock.

In addition to standards, it provides the building blocks to making renovation realistic and accessible to those who need it most. This is particularly the case for the reform of Energy Performance Certificates, Renovation Passports, and financial support schemes. The measures are clear, ambitious and mutually reinforcing, which will trigger action and create certainty for the long-term. This is what Europe needs.

Ultimately, the question comes down to what kind of future we want. Are we serious when we say we mean to fight climate change, reduce energy bills and achieve energy independence?

If the answer is yes, then we challenge our co-legislators, particularly Member States: Grossly oversimplifying the EPBD for the sake of popularity at home is weak and will not solve the complex problems you are facing. It is time for bold action and political courage.

A strong EPBD will help bring about the meaningful change citizens are waiting for.